By Fedima

How to handle enzymes safely so that production teams remain free of respiratory issues and the products fully benefit from their functionality? This research is at the top of the list this year for Fedima’s Enzyme Expert Group. The European association representing the bakery, patisserie and confectionery ingredient manufacturers researches best practices and shares guidelines.

Flour and enzymes play essential roles in the baking industry. Flour dust, containing approximately 40 different protein allergens, can cause respiratory allergies and ‘baker’s asthma’. Enzymes, like other proteins, may act as respiratory sensitizers when people are repeatedly exposed to airborne dust containing them. Proper monitoring, process controls, product formulation, and appropriate handling instructions can significantly reduce the risk of worker exposure.

Introduction

Enzymes form a special class of proteins, produced by in all living organisms. Proteins are naturally produced by all living cells; all living organisms need enzymes to conduct virtually all the physiological processes essential for life. They act as biocatalyst in physiological processes essential for life, speeding up chemical reactions. For instance, amylases in saliva begins the process of breaking down starch in smaller pieces so our bodies can absorb them. Bakers have learnt to use enzymes in bread making and benefit from them for centuries.

Industrial enzymes have low toxicity in humans; i.e. enzymes present no concerns in terms of acute toxicity, genotoxicity, sub-acute and repeated dose toxicity, reproductive toxicity and carcinogenicity. (1)(2)(3) However, like many other proteins, enzymes may act as allergens via inhalation.

Allergy symptoms may be similar to those of the common cold, and if such symptoms occur frequently at the workplace and only rarely at weekends or during holidays, they may be the result of occupational enzyme exposure. Allergy by inhalation caused by flour or enzymes is similar to the respiratory allergies caused by well-known allergens like grass-pollen, with similar symptoms as well. There is no scientific evidence that enzymes are associated with allergies caused by skin contact or ingestion. (4) (5) In general, minimizing flour and enzyme dust exposure in bakeries, flour mills, and bakery ingredient manufacturers will reduce the likelihood of work-related respiratory symptoms.

Inhalation allergies develop in two steps: sensitization and elicitation, with symptoms appearing upon repeated exposure to high airborne concentrations of the allergen. Symptoms of allergy to enzyme/flour dust, similar to those of common cold, include itching nose and eyes, nasal and sinus congestion, sneezing, coughing, hoarseness, chest tightness, and shortness of breath.

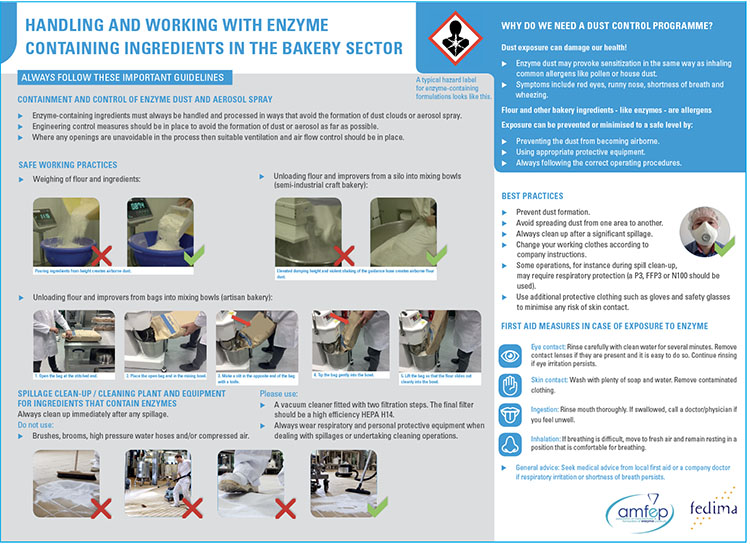

AMFEP and Fedima have developed guidelines for safe handling of raw materials and ingredients containing enzymes to safeguard the health of workers in the bakery supply chain.

Further reading

The paper, “Industry Guidelines On the Safe Handling of Enzymes in the Bakery Supply Chain”, was developed by the joint Enzymes Safety Working Group, made up of members of the Association of Manufacturers and Formulators of Enzyme Products (AMFEP) and the Federation of European Union Manufacturers and Suppliers of Ingredients to the Bakery Confectionery and Patisserie Industries (Fedima).

Control measures

Several measures should be simultaneously taken to prevent exposure to enzymes, starting with preventing dust formation by plant design, and including prevention of aerosol formation. In addition, dust/aerosol formation should be contained at the source, by using completely closed systems. Spillage throughout the process should be avoided. The design of the equipment used in the production chain should also support safe handling. Moreover, comprehensive training is a must, so that production staff is provided with clearly described guidelines and standard operating procedures.

The following control measures can be considered to prevent exposure:

+ Eliminating or substituting risk-prone materials and ingredients is the most effective step to prevent flour and enzyme dust formation. Since flour and enzymes are vital ingredients in any baking process, this measure does not directly apply. Historically, the baking industry first used enzymes produced in powdered form, and then gradually evolved towards using granulated or liquid formulations to reduce the risk of dust creation and inhalation

+ Isolation, enclosure and ventilation: these measures are applied when using closed systems for the transport and storage, and the blending and mixing of wheat flour and additional ingredients, including enzymes. NB: these measures may only be applicable in larger manufacturing units and large-volume production operations.

+ Mechanical control measures, including local exhaust ventilation, vacuum cleaning and protective equipment.

+ Respiratory Protective Equipment (RPE) or Personal Protective Equipment (PPE), including protective clothing, should be considered as a last resort of control; e.g., in specific situations with high risk of exposure or in case of emergencies. Face masks (FFP3) are in common use to protect against dust inhalation.

Exposure control in industrial bakeries

All exposure control measures should be based on risk assessment of the work place and deal also with GMP.

As it is automated to various degrees, industrial bakery manufacturing frequently includes the use of silos and closed dosing systems, which greatly reduces the exposure risk of the rest of the staff to possible dust formation. Very often, only one or two people are responsible for each process step.

Dust formation can still occur when filling and refilling small silos with dust-forming raw materials from big bags. In this case, specialized equipment should be used, to move materials from the big bag through an almost closed system into the silos. Nevertheless, since this is not a completely closed system, dust can form. It should be noted that, when using a system in which the inner big bag liner seals to the discharge equipment before the bag is opened, there is no spillage. Since the inner liner is sealed before automatically discharging the materials, handling materials that can create dust becomes entirely safe. However, the use of closed, automated dosing systems tends to be limited to large throughput and high-volume processes due to their cost.

Some bread specialties are still made with bagged powdered ingredients and additives. Occasionally, additives, ingredients and processing aids are used in liquid form, which makes automated dosing much easier and considerably reduces dust levels. However, the formation of aerosols is a serious risk to consider in such cases. Water and yeast are added through dosing pipes to the mixing bowl. Once the dough has been mixed, there is no further risk of enzyme dust formation.

When flouring conveyor belts to prevent dough from sticking, the flour is dispersed from low heights with minimal force, so dust formation at this step is negligible. The potential for enzyme dust formation is also very low.

1. Storage: silos are preferred and, when this is not applicable, there should be dedicated storage areas for bags of enzymes. Open bags should be sealed and portable vacuum cleaners should be used to clean up spillages.

2. Dry bulk ingredient weighing: closed systems should be used as well we local ventilation systems, placed above or behind the mixing bowl.

3. Weighing: some formation of dust will always occur at this stage, which is why a ventilation system at the weighing station is recommended. In the absence of automated ingredient delivery, local ventilation significantly reduces exposure to flour and improver dust. Respiratory protection equipment (RPE) should also be used.

4. Loading/unloading dry ingredients into the mixing bowl: when dry materials are manually delivered into the mixer, they should be slowly released from the bag. Making a slit into the bag at the opposite side from the opening will help dry materials slide out easier while avoiding shaking to bag. A local exhaust system should be put in place, above or behind the mixer. When dry materials are delivered from a silo, it should closely fit the mixer to avoid dust formation.

5. Dough preparation: as the biggest concentration of dust is bound to be created at the start of the mixing process, mixing bowls with a lid should be used. If the mixer features a grid-type cover, an extraction system should be installed. Adjusting mixing speeds also minimizes dust formation, by starting the mixing process at a slow speed and increasing it when all the dry and wet ingredients are blended. It is also recommended to limit the use of dusting flour in the mixing bowl and use a small amount of oil instead, at the end of the mixing process, whenever the product allows it.

6. Dough handling: automatic flour dusters usually disperse flour onto the conveyor belt to prevent the dough from sticking. If set correctly, they will only drop flour where it is needed and will do so in a way that does not lead to creating dust clouds. Workbenches made of materials such as inox, stainless steel and polyethylene should also be used, as the need for dusting flour spread is greatly reduced.

7. Waste: packaging should be collected as soon as it is empty, in plastic bags if they were used to store powders.

8. Ventilation: filtration systems used in industrial bakeries can be quite sophisticated. At a minimum, the standard of filtration required is F8. After filtration, the extracted air should be discharged outside of the building, to prevent dust formation inside the facility.

Reducing dust exposure: practical steps

Purchasing: wherever possible, non-dusty raw materials should be sourced. For example, liquids, pastes, or grades of powdered ingredients that have large particle sizes should be selected, or materials that have been treated to minimize their capacity for dust creation.

Goods inwards: enclosed pipes are recommended, whenever possible, for the intake of dusty raw materials. Otherwise, puncturing or rupturing the packaging of powdered materials should be avoided. To further protect it, storage pallets should be undamaged and free from splinters.

Debagging/unboxing: staff should be trained and encouraged to unpack powdered materials in a way that doesn’t create dust clouds (e.g., bags of powdered ingredients/flour should not be shaken from heights). A standard operating procedure is recommended when handling partly used bags, to carefully close, reseal and store partly used bags of enzyme-containing ingredients to minimize dust formation. All such bags should be stored in an area with easy access for the safe cleaning of any accidental spillage.

Using face masks, safety goggles, gloves, respirators, etc.: staff members should be aware that the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) still means they should handle powdered materials carefully. PPE is intended to minimize risks, not ensure protection from clouds of dust that are created by careless handling.

Extraction and ventilation: make appropriate use of extractors and ventilators in areas that may be particularly susceptible to a dusty atmosphere; e.g. in weighing, mixing and blending areas.

Spillages: vacuum cleaners fitted with appropriate HEPA filters should be used when handling dusty material spillages, while also ensuring that the vacuumed contents do not create dust clouds when emptied. Where dust is required during a process (e.g. when producing bread or pastry on an automatic line), equipment that drops flour only where it is needed should be used. If excess flour dust needs to be removed at any stage, an extraction unit should be installed over the line, or suitable guards to prevent dust from being discharged into the atmosphere. If possible, ‘non-dusty’ flours should be used for this purpose. Spillages should be addressed as soon as they occur.

Air monitoring

Monitoring should be prioritized based on the risk of exposure to workers. The basis for the sampling strategy in workplace air is the EN689 standard. Routine air sampling is a quantitative tool to measure levels of background exposure to enzymes and dust, whereas peak sampling is used to measure high-risk exposures. Air monitoring can be undertaken with either high- or low-volume samplers.

Area sampling is used to evaluate the effectiveness of control measures and trends in performance, and is typically done at a fixed location; it can readily provide an indication of employee exposure. The personal exposure level is typically a factor 2 to 5 higher, depending on the direct tasks.

Personal sampling involves a sampling train (pump-tubing-sampler-collection substrate). Low-volume devices are primarily used, but there are also wearable high-flow pumps on the market. However, the use of personal sampling is limited.

It is good practice to measure both total inhalable dust and enzyme airborne dust in the bakery supply chain. Only enzyme aerosol levels are measured in liquid operations. As the limit values are mainly for the inhalable fraction, an inhalable aerosol sampler should be used. Enzyme suppliers can be contacted for advice on measuring inhalable enzyme dust.

Health surveillance

There are two toxicological end-points as a consequence of enzyme dust exposure: respiratory allergy, which is an intrinsic hazard for all enzymes, and skin irritation, which is an intrinsic property of enzymes belonging to the class of proteases. In addition to alpha-amylases and glucoamylases, other enzymes may be used in bakery, such as cellulases, lipases, xylanases and proteases. The main safety concern associated with enzymes is their potential to induce respiratory allergy, as these effects are practically irreversible.

Unfortunately, the relationship between airborne exposure to enzymes and the development of sensitization or allergy is still poorly understood. Although enzyme formulations have recently been improved, changing from very dusty powder to less dusty granular, paste-like and even liquid enzyme formulations, there are still situations where the number of enzyme allergies is on the rise due to the lack of awareness among workers and poor management.

Workers potentially exposed to enzymes should undergo medical examinations periodically, according to what is established by the risk assessment of the specific work-place and following legal obligations. Health surveillance is highly recommended for all employees in the bakery supply chain who may be exposed to flour and bakery ingredients, especially enzymes.

During the first 24 months of employment, workers should have six-monthly health surveillance checks and thereafter a minimum of every 12 months. The review should include a periodic respiratory questionnaire, spirometry and an immunological test. Those with normal findings may continue to work until the next examination. Those who have developed a positive immunological test result to enzymes and have no other adverse findings may continue to work with enzymes, although an increased frequency of medical surveillance of such workers may be appropriate.

Those with abnormal findings to the respiratory questionnaire which could be due to enzymes and those with impaired lung function should immediately undergo further assessment. They should also be re-tested within one month or at the discretion of occupational health professionals. Those who show a continuing downward trend in lung function should be carefully assessed regarding the need to remove them from further work with enzymes.

It is important to emphasize that the risk of respiratory sensitization to enzymes is solely occupational. Enzymes used in the bakery industry will be denatured during the baking process and eubsequently lose their potential sensitizing capability. Additionally, enzymes are in general not associated with food allergies (allergy as a result of oral exposure).

The ‘Industry Guidelines on the Safe Handling of Enzymes in the Bakery Supply Chain’ paper is available for in-detail consultation on Fedima’s website (https://bit.ly/enzymesafety).

References:

1. Basketter, D.A., Berg, N., Kruszewski, F., Sarlo, K.S., 2012. The toxicology and immunology of detergent enzymes. J. Immunotox., 2012; 9(3): 320-326

2. Basketter, D.A., Berg, N., Broekhuizen, C., Fieldsend, M., Kirkwood, S., Kluin, C., Mathieu, S., Rodriguez, C., 2012. Enzymes in cleaning products: An overview of toxicological properties and risk assessment/management. Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology 64 (2012) 117-123

3. Basketter, D.A., Broekhuizen, C., Fieldsend, M., Kirkwood, S., Mascarenhas, R., Maurer, K., Pedersen, C., Rodriguez, C., Schiff, H.E., 2010. Defining occupational and consumer exposure limits for enzyme protein respiratory allergens under REACH. Toxicology 268, 165-170

4. Basketter, D. A., English, J. S. C., Wakelin, S. H., & White, I. R. (2008). Enzymes, detergents and skin: facts and fantasies. British journal of dermatology, 158(6), 1177- 1181.

5. Bindslev-Jensen, C., Skov, P. S., Roggen, E. L., Hvass, P., & Brinch, D. S. (2006). Investigation on possible allergenicity of 19 different commercial enzymes used in the food industry. Food and chemical toxicology, 44(11), 1909-1915.