How to better meet today’s customer expectations with modified dough processes for baked goods containing rye.

Current technical literature describes that when the total grain content is made up of 20% or more rye flour, the use of sourdough and/or acidifying additives is technologically necessary, i.e., to achieve an elastic and loosened bread crumb. However, it has been known for over 20 years that even 100% rye flour of average quality can be baked with a largely elastic crumb without the addition of acid. In practice, it is rightly avoided because of the poor bread aroma and taste and the lack of freshness. How much acid is required to bake rye-based products and which dough processes are important? Explanations are below.

The basics

Two parameters are used to characterize acids in foods, pH value and acidity, which are usually determined in aqueous solutions. The pH value is a measure of the strength of an acid; it describes the dissociated (exposed) hydrogen ions (H+). The degree of acidity, alternatively, indicates the amount of acid and describes both the dissociated and the undissociated (bound) hydrogen ions. Figure 1 shows an example of which hydrogen ions are detected by acetic acid (CH3COOH) to determine the pH value and acidity.

To determine the pH value, 10 g of sourdough or bread crumb is mixed with 5 ml acetone and approx. 40 ml of a total of 100 ml distilled water to form a homogeneous slurry. The slurry is then transferred to a beaker with the remaining 60 ml of distilled water. The pH value in the aqueous solution can now be determined using the measuring electrode of a pH meter. If the acidity is also to be measured, the aqueous solution is titrated with sodium hydroxide solution (0.1 mol/l) until a pH value of 8.5 is reached. The consumption of sodium hydroxide (0.1 mol/l) in ml/10 g sample, which is necessary to neutralize the acid in the aqueous solution, corresponds to the degree of acidity (Brand & Gänzle 2006; Meißner 2016). Figures 2, 3, and 4 show guide values for pH and acidity levels of various sourdoughs, bread doughs and bread types.

In Germany, pH and acidity are usually also used to assess bread quality. The general rule here is that the higher the proportion of rye-milled products and, in particular, the use of dark and coarse-milled products, the higher the bread acidity. The technologically required level of acidity of the bread is also determined by the dough yield, dough inserts and baking time, with which it is directly proportional. If a slow temperature rise in the center of the crumb is to be expected due to the shape of the bread or the use of baking tins, a higher amount of acid and thus a higher degree of acidity is also required.

In general, less sour breads and pastries are increasingly preferred. This does not necessarily mean that bread aroma and flavor should be less expressive. The fermentation processes in the sourdough and bread dough as well as the additional precursors introduced influence the result and the length of the total processing time.

Full leavening management

The three-stage full sour method is considered the ‘supreme discipline’ in the production of mixed rye bread, rye bread and whole rye bread. The relatively mild souring ensures the necessary amount of acidity and the correct ratio of lactic and acetic acid, the formation of the aroma precursors, dough rise and a high proportion of pre-soaked ground cereal products. This is reflected positively in the overall bread quality accordingly.

The amount of rye flour to be acidified from the total flour of the bread dough is relatively high due to the low acidity of the full sour, which results in fresh bread with a very good flavor. The temperature, dough yield and maturing time of the individual stages are coordinated in such a way that, in addition to the lactic acid bacteria, the sourdough yeasts also multiply, which contributes significantly to the loosening of the dough and thus, with correct sourdough management, enable the production of breads without the addition of yeast. The sourdough yeasts also contribute to flavor formation.

Basically, a distinction is made between two variants of three-stage method (Figure 5). If a mature full sourdough from the three-stage process is to be available for processing at the start of work, the full sour method overnight is used with a full sour maturing time of 8 – 10 hours. If this is not necessary, the basic sour is kept overnight and the full sour is only run in the morning at the start of work, which is then available after a three-hour maturing time.

Full sour must be processed relatively quickly, as the processing tolerance of the active full sour is very low. The starter material for the next sourdough preparation is taken from the mature full sourdough and stored in cold storage until further processing.

The respective maturing time of the individual sourdough stages determines their proportions in relation to each other. The amount of flour to be leavened per sourdough stage can be calculated using the IREKS multiplication rule. According to it, the flour quantity in the individual stages is divided by the number of hours in the maturing time for this stage.

A reduction in the proportion of sourdough is easily possible with smaller dough batches by extending the resting time of the dough and the loaf proofing time. This results in better swelling of the added rye and wheat flours, while allowing them to ferment longer.

Example of the calculation of a three-step guide for the production of mixed rye bread 70/30

Acidification is carried out via a three-stage method (basic overnight acidification). The TA of the full souring is 180 and the acidity should be 11 – 13. A recipe is prepared with 100 kg of to-tal flour. For a 70/30 mixed rye bread, 70 kg of rye flour is available. For a medium acidification intensity, it is recommended to acidify approx. 50% of the rye flour quantity (Brandt & Gänzle 2006).

Based on 36 kg of rye flour to be soured and the data on the maturing time and dough yield from the ‘Three-stage process with basic overnight souring’, the respective amount of flour for the individual sourdough stages can be determined using the IREKS multiplication rule. Figures 7 and 8 show how the required amounts of rye flour and water are added in each stage.

With the 36% acidified total flour (calculated as rye flour), the rye can be reliably acidified with the specified dough yield and the acidity of approx. 12; a firm and elastic crumb can be achieved even with thick dough layers or tin bread. A reduction in the proportion of sourdough is easily possible with smaller dough batches by extending the resting time of the dough and the loaf proofing time. This results in better swelling of the added rye and wheat flours, while allowing them to ferment longer.

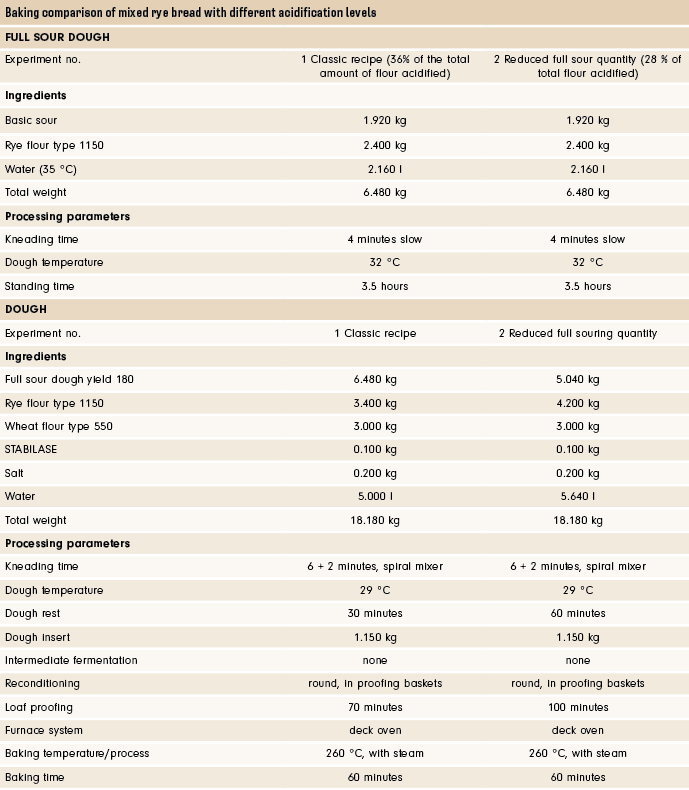

Baking comparison of mixed rye bread with different acidification levels

The mixed rye bread with the reduced full-sour content and the resulting longer processing times is characterized by a milder and more aromatic odor and taste as well as a somewhat juicier crumb.

Pumpable rye sourdoughs

In the case of liquid or pumpable rye sourdoughs, a distinction can be made between mild full sourdoughs (dough yield 210 – 230) and long-term sourdoughs (dough yield 200 – 220). While comparatively high quantities can be used with full sourdoughs with acidity levels of 13 – 15 and pH values of 3.8 – 4.1, the application quantity, respectively the quantity of pre-swollen flour is significantly reduced with long sourdoughs with acidity levels of 25 – 30 and pH values of 3.5 – 3.9.

Particularly in the warm season, the acidity levels of long-term sourdoughs rise to values well above 30 in acidity levels. This often leads to over-acidified breads with poor freshness. In addition, breads made from long sourdoughs with relatively high yeast additions of 1.5 – 2.5% lack flavor.

In view of the average rye flour quality of recent years and the preference for mildly acidified but still aromatic bread, it is recommended to critically examine sourdough proportions. A reduction in sourdough proportions in conjunction with using somewhat less yeast and extended dough processing is an important approach to increasing bread quality.

Changes in rye flour quality

Since the early 1970s, hybrid rye varieties, a cross between two rye varieties with defined characteristics, have been increasingly cultivated. These new varieties are more

resistant to sprouting, have higher yields and are also lower in enzymes than earlier rye varieties. They have greatly contributed to mitigating sprouting damage, to the point where it is no longer a major issue today. The changes in the quality of rye flour become clear when comparing falling number and amylogram values from 1960 with today’s values.

Due to their lower enzyme activity and the corresponding properties of the starch, today’s rye flours more often lead to defect patterns such as too low bread volume, poorly loosened, dry crumb with drying cracks, and poor bread freshness retention, even though the new rye varieties absorb up to 10% more water than the varieties of 60 years ago.

In the past, the most important task of sourdough was to ensure rye ‘bakeability’, i.e. the formation of a closed and elastic bread crumb. With the new rye varieties, the main aim is to optimize the crumb properties; not so much acid is needed anymore. To improve the bread freshness and aroma of rye and mixed wheat breads, the traditional sourdough processes can be adapted accordingly.

To this end, attempts are made to introduce a higher proportion of pre-fermented flour ingredients into the bread dough in order to increase the flour’s own enzymatic activity. This improves the freshness and crumb structure of the breads. It is achieved by adding higher amounts of sourdough with a lower acidity level. To avoid too rapid and too strong acid formation, low starter quantities and batch temperatures should be used. In the case of bread doughs, care should be taken to ensure that the dough temperatures do not exceed 28 °C and that the quantity of yeast used is not too high.

To be able to produce high-quality breads with a moist crumb and good freshness retention, when processing rye flours with low enzymes, specially developed baking agents should be added, or malt flour and/or malt extract. The wide range of malt varieties available today makes it possible to develop new quality breads with a strong character and to differentiate them from the existing bread varieties.

Boiled grain made from flours and coarse grain can also help optimize the swelling of milled rye products, improving moisture. However, the dough yields should not be allowed to become too high.

Rye predoughs with dough yield of 200 – 220, yeast additions of 0.2 – 1.0% on rye flour and a resting time of up to 15 hours are also suitable for increasing juiciness and optimizing the flavor profile of breads containing rye.

Rye breads, minus baker’s yeast

The production of breads containing rye without the addition of classic baker’s yeast is another emerging trend. With the help of the mild Lievito Madre, fluffy, juicy breads with a pronounced taste can be baked.

Leavening mixed rye breads with a rye content of 60% or higher is certainly possible using the three-stage full sourdough process, without the addition of baker’s yeast. However, baker’s yeast is additionally required for higher wheat percentages. Otherwise, the acid content becomes too high. Alternatively, fermentable Lievito Madre can be used.

Originally from Italy, Lievito Madre (mother yeast) or Lievito Naturale (natural yeast) are ideal for good swelling and fine fermentation flavors in bread thanks to their mild acidity and raising power. The yeasts contained in Lievito Madre come exclusively from the multistage long fermentation of wheat flour and water. This is often in line with the wishes of discerning customers and can be used in advertising for certain types of bread with long fermentation times. With the Lievito Madre, a high proportion of the wheat flour used is also fermented for a long time.

Conclusion

The rye flour and wheat flour characteristics available today enable the production of less acidified rye, mixed rye, mixed rye and mixed wheat breads. Adjustments in sourdough proportions, yeast additions, maturing times, and fermentation times, as well as the use of unleavened precursors, make it possible to produce breads with complex fermentation flavors. In addition, the often desired more open pores and juicier crumb can be produced. If the breads are baked with intensity, a strong aroma and taste are obtained. A self-critical examination of bread quality is not only worthwhile when individual bread types experience a decline in sales. The past 24 months have clearly shown that bread efficiency is very important, even when bread sells well overall.